Code as a Liberal Art, Spring 2021

Unit 3, Exercise 1 lesson — Wednesday, April 14

The hyperlink, HTML, and CSS

In the final unit of the semester, we are going to experiment with techniques in digital publishing, that is, presenting texts and other cultural objects within digital media. More specifically, we'll be working with hypermedia (a.k.a hypertext — I will use these terms basically synonymously), and creating HTML & CSS pages. Hypermedia can mean many things but we can define it simply as: documents that contain an assemblage of multimedia objects connected together via clickable links. By multimedia here I'm referring to text, images (photos or others graphics), sounds, videos, and even games or other interactive elements. Today we will learn the basics of working with hypermedia by working with HTML & CSS.

There have been other forms of hypermedia in the past (HyperCard, CD-ROM interfaces) and there are others today (one could argue that many different video games are their own kind of hypermedia interfaces) but by far the dominant, ubiquitous form of hypermedia today is the HTML & CSS that exists on the web. As a human being in the 21st century with access to technology, you are of course already well-versed in what HTML & CSS are, how to use them, and the basics of how they work. Many of you have already built websites using platforms like Wordpress, Squarespace, or Wix, and many of you have already hand-coded HTML pages yourselves. As with earlier parts in the semester, I hope this unit is a process of defamiliarization that creates an opportunity: to reconsider something of the digital that you may already knew but in a new way, to create some distanciation between us and our assumptions about these objects and how they work, to situate them within historical contexts so we can recognize their contingencies and think about how they could have been done differently, and to develop a deeper understanding of the mechanics of how they work.

Screenshot of Douglas Engelbart working with

nonlinear text during "The Mother of All Demos", 1968.

Screenshot of Douglas Engelbart working with

nonlinear text during "The Mother of All Demos", 1968.

Background and context

HTML and CSS are the main languages of the World Wide Web (a.k.a. the web, a.k.a. WWW). The web is a collection of interlinked files, usually called pages, which are stored on servers around the world. The web is basically everything that you view in your browser. The web is not computer programs or applications that you download and run on your computer, nor is it the apps that you download and run on your phone. Although, some apps on your phone are web-based, in that they operate like little browsers that just view web pages.

We will start this unit by creating web pages as files that you will save and view only on your computer without using any other computers or any networking. This is often called working locally. Next lesson, we will learn how to upload these files to other computers called servers. Servers are computers just like yours, but they exist physically in data centers, they are always on and connected to the internet, and if you upload your files to a server, they are able to be viewed by other people any time. This is how web sites are made.

HTML stands for "Hypertext markup language", and CSS stands for "Cascading Stylesheets". Together, these two languages comprise almost all of the files on the world wide web. HTML and CSS are usually created in separate files, which are indicated by file extension in their filenames. File extensions are the characters that come after the dot (the period) in a filename. When working with HTML and CSS, as with Python and other coding work, you have to be careful about your filenames. HTML files will end with ".html", for example "rory-page.html"; and CSS files will end with ".css", for example "rory-styles.css".

Important rule: When naming your files for this unit, use only lowercase letters, numbers, hyphens (-), and underscores (_), and always make sure your filenames end with either ".html" or ".css". Do not use spaces in filenames, and do not use capital letters. Filenames for this unit will be case sensitive. That means if you use any capital letters in your filename, you will get errors and your site will not work.

Since the "ML" in "HTML" stands for "markup language", technically speaking we wouldn't say that HTML is a programming langauge. Rather it is a language that describes the structure and content of documents, and together with CSS, they describe the appearance of documents as well.

As we discussed last class and above, hypermedia is comprised of pages connected together via hyperlinks often just called links. One thing I wish to emphasize here is that a link is interactive. We almost take for granted the user action or gesture of clicking on a link, but keep in mind that a link is a bit of text that responds to some user input in a way: it responds to a mouse click by calling up a different document for display. Later in this unit we'll use Javascript to implement techniques for handling all sorts of other, perhaps more exciting user gestures. But keep in mind that a clickable link is the default interactive user interface object of hypermedia.

The link is the fundamental element that stitches together the web. A link is the primary technique that will allow your user (in this case now variously also called a viewer, reader, or audience) to navigate a collection of documents in a nonlinear way.

Since a webpage can (and usually does) contain links to more than one other webpage, we often say that hypertext is nonlinear, meaning you can use hypertext to construct branching and forking narratives, can allow a user to click directly in to references or citations or support materials, or can present an argument as an overview with links drilling down into specific substories or subarguments

Today we will start with the basics of HTML and how to create HTML files (pages), then learn how to include image files and how to make links. Next week we'll learn about controlling the appearance of these pages with CSS and adding other mutimedia, and learn how to upload these files to a server so that others can view your work. After that we'll introduce Javascript and implementing more sophisticated user interaction.

Let's get started ...

First HTML page

Let's create our first HTML page. I've created an HTML template here that you can use to start all of your HTML files for this unit. Copy/paste the following into Atom:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <title></title> <link rel="stylesheet" href=""> </head> <body> </body> </html>Now click File > Save (you can also type ⌘S on Mac). In the filename box (where it says "Save as") type "index.html" exactly as I have here, lowercase, no spaces, with the filename extension, then navigate to the Exercises folder in your Unit 4 folder, and click Save. You have just created your first HTML file.

Now, if you go into Finder, navigate to the folder where you just saved that file, and double-click on the file, it should open up as a blank page in Safari (or your browser of choice). If you see this, it means all is working properly. If you don't, it means there is an issue. Please read over the above instructions carefully and double-check your filename.

Leave this web page open in your browser. We will come back to it and reload as we add more HTML.

HTML syntax

So far this semester we've looked at code syntax for two languages: Python and HTML. They are quite different from each other owing to the two very different tasks that they were each designed to do. Python uses variables and control structures to construct algorithms, while a markup language like HTML uses tags to indicate format and structure of bits of text within a document.

We already talked a bit about HTML syntax in Unit 2, so this is a bit of a review and a more focused consideration of HTML syntax rules.

These are called braces: < >

They must always appear in pairs. We call the left

brace open and the right one closed, so we can say they must

always appear as open and closed pairs.

We say the stuff in between the braces is inside the braces. The stuff inside braces determines an HTML tag. There are many many HTML tags. We will learn a few today, and a few new ones in each lesson. We will have time to get through only a very tiny fraction of all tags that are available. As a way to learn more, and as a great reference, I highly recommend W3 Schools

The code snippet above contains four tags that we'll talk about now:

- an

<html>tag - a

<head>tag - a

<title>tag - a

<body>tag

(Let's ignore the <link> tag. We'll come back

to that next week.)

(Our snippet also contains a single DOCTYPE

tag. You don't have to worry about that beyond making sure to

always include it as the first line of your HTML files. That

simply tells our web browser what type of document this is. In

this case, HTML.)

Most (but not all) HTML tags must come in pairs that we call

open and close tags. Close

tags are indicated with a slash /. In the above

code snippet, four HTML tags come as open and closed

pairs: <html>, <head>, <title>,

and <body>; while two do

not: <DOCTYPE>

and <link>.

Let's add some new tags and textual content to our first web page.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title></title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello</h1>

</body>

</html>

I have just added a new tag called an <h1>

tag. As you can see, it comes as a pair of open and close

tags, and each tag is written with a pair of open and close

braces. In between the two tags is some text. We say that this

text is inside the tag. In this case I have added the

word Hello inside my <h1> tag.

Save your file, go back to your browser, and click File > Reload, or you can type ⌘R on Mac. You should see the word 'Hello' in your browser.

Some other tags that you can play with are <h2>,

<h3>, and <h4>

tags. These all add "headings" of various sizes. You can also

create a <p> tag and

a <div> tag. This creates a

"paragraph". This will not look different right now, but in

the coming lessons you will see why they are useful. Try

playing around by adding a few other tags with some additional

text inside them. Make sure all your new additions are inside

the <body> tag. Save your work, go back to

your browser, and click File > Reload (⌘R on

Mac) to see your work.

At this point your file might look something like this:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <title></title> <link rel="stylesheet" href=""> </head> <body> <h1>Hello</h1> <h2>This is my first webpage</h2> <p>Here is a bunch of text in a paragraph.</p> </body> </html>

Adding images

There are two more tags I want to show you today.

The first one will let you add images into your pages, and that

is the <img> tag, which (predictably) stands

for "image". This has some more complicated syntax and looks

like this:

<img src="filename.jpg" />Note the slash before the closing brace.

<img> tags do not come in

pairs. They do not have a closing tag. Instead, they have this

slash to indicate there is no other closing tag.

We have added a new thing here which is called

an attribute. The attribute here is

named src and its value

is "filename.jpg". Any given HTML tag can

potentially have many attributes. In fact you

can think of the attributes as our old friend from Unit 2:

the key-value pair. In HTML,

the key-value is indicated with an equal

sign =. You can probably see here how if you were

implementing a web browser in Python, you might use a dictionary

to implement all the key-value pairs for a

given HTML tag.

This particular attribute, src, is used to indicate

the path and filename for the image that you want to embed in

your page here.

Make a new subfolder within the folder you're working with and

call it images. Now, move or copy an image into

that new folder (if you need to, make sure to rename it to

remove any spaces and uppercase letters in the filename), and

type the filename exactly as it is into the attribute,

making sure to specify the subfolder name first, followed by a

slash. For example:

<img src="images/engelbart.png" />

You can add this to your HTML file anywhere inside

the body tag. I'll put mine here:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title></title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello</h1>

<h2>This is my first webpage</h2>

<p>Here is a bunch of text in a paragraph.</p>

<img src="images/engelbart.png />

</body>

</html>

Save your file, return to your browser, and reload to see your

image.

If your image is too large, you can resize it with some additional attributes like this:

<img src="kite.jpg" width=600px height=600px/>

Note that if you specify both width

and height, and if the ratio of width to

height is not the same as the original image, you will get

some stretch or distortion in the way the image is

displayed. As a solution, you may use

only width or height, which

will set that dimension of the image, and automatically scale

the other dimension proportionally to the original, without

distortion.

Adding hyperlinks

OK! We're finally ready to add a hyperlink.

To do this, we first need to create a second page to link to. In Atom, click File > New File (⌘N on Mac). You can copy/paste the code from the empty HTML page template that I provided, or copy paste the following code:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <title></title> <link rel="stylesheet" href=""> </head> <body> </body> </html>In general, whenever you start a new page, you should start with this and add any new markup inside the

<body> tag. Add some other content to

this file. I'll add some text like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title></title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="">

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is my second webpage!</h1>

</body>

</html>

Then save the file. Click File > Save (⌘S on Mac), browse

to the folder where you have been working, type a filename and

click Save. You can name your file whatever you'd like. I'll

call mine page2.html.

Now let's add a link. The syntax combines everything we've talked about so far: open and close tags, and attributes. Like this:

<a href="page2.html">click here</a>The attribute here is named

href

and it specifies the filename of the page that we will be

linking to, and the text inside the

open and close tags specify what the user will see and what

they will be able to click on.

Add that to your file somewhere and you should have something like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title></title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello</h1>

<h2>This is my first webpage</h2>

<p>Here is a bunch of text in a paragraph.</p>

<img src="kite.jpg" />

<a href="page2.html">click here</a>

</body>

</html>

Save this file, go back to your browser, reload, and try

clicking on your link! You can use your brower's Back

button to go back to the previous page.

Now try adding a link from page2.html that points

back to index.html

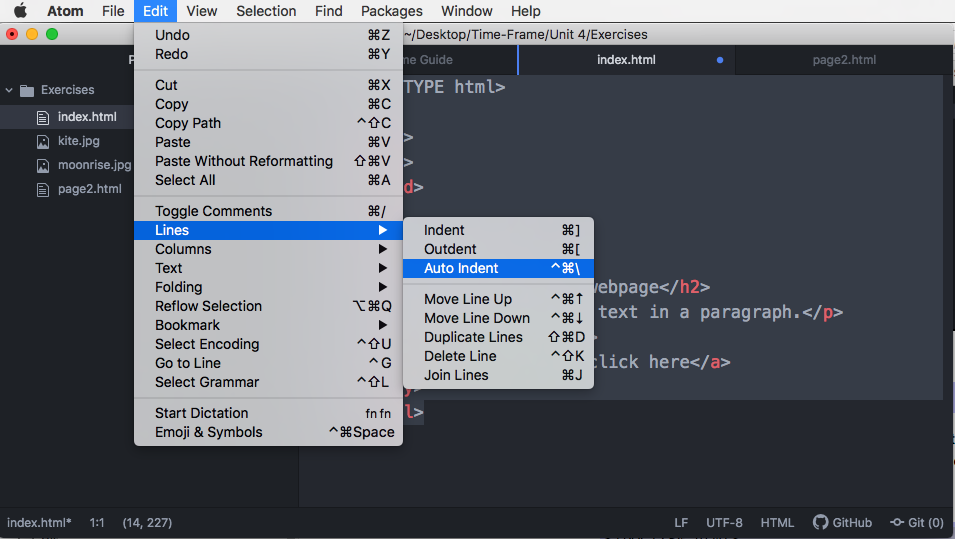

Useful tip: When you are working doing HTML coding (or any kind of coding) you should use your text editor to auto-indent frequently. In Atom, you do this by selecting all the text (Edit > Select All or ⌘A on Mac), and then clicking Edit > Lines > Auto Indent (or ^⌘\ on Mac). Do this frequently! It will help you see what tags are inside what other tags. Like so:

Sitemaps and Wireframes

We've already been working quite a bit with sitemaps: they were the network diagrams that you were generating algorithmically with your web scraping / web crawling code!

In this unit, sitemaps will be less something to reverse engineer from an existing website, but rather something that you will generate in creating a web of relations in the nonlinear presentation that you will be crafting.

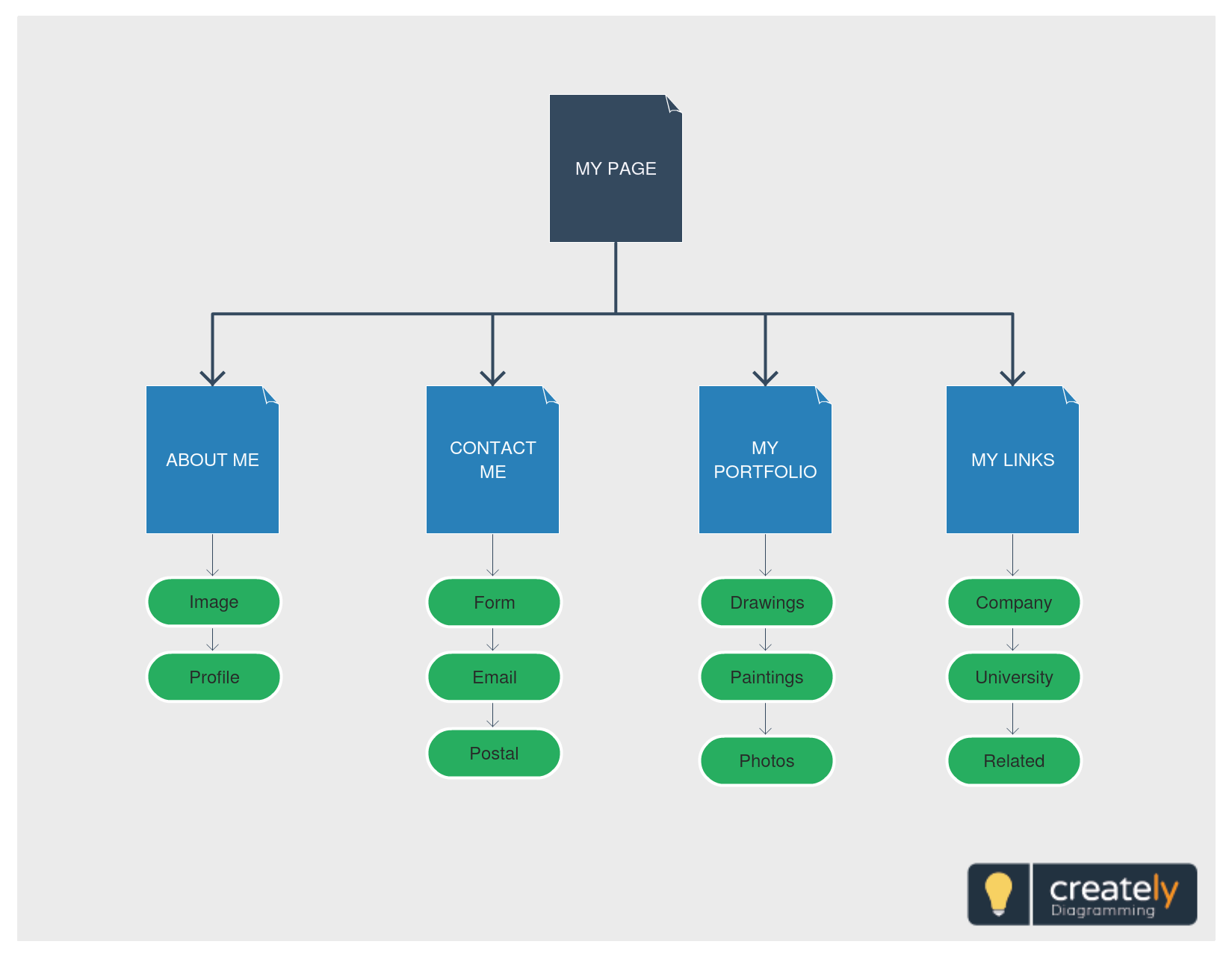

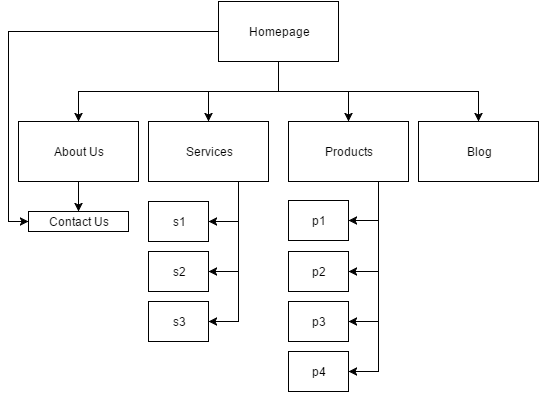

In this register, a sitemap is a technique of planning, like an outline for an essay: a practice of analytical diagramming that creates a visualization of the link structure of the content of a website. A sitemap will typically represent each page as a simple square or rectangle, and links will be represented as lines, with lines connecting which pages link to which others. Sometimes these lines can be pointed arrows, indicating which way the link goes. Here are two examples:

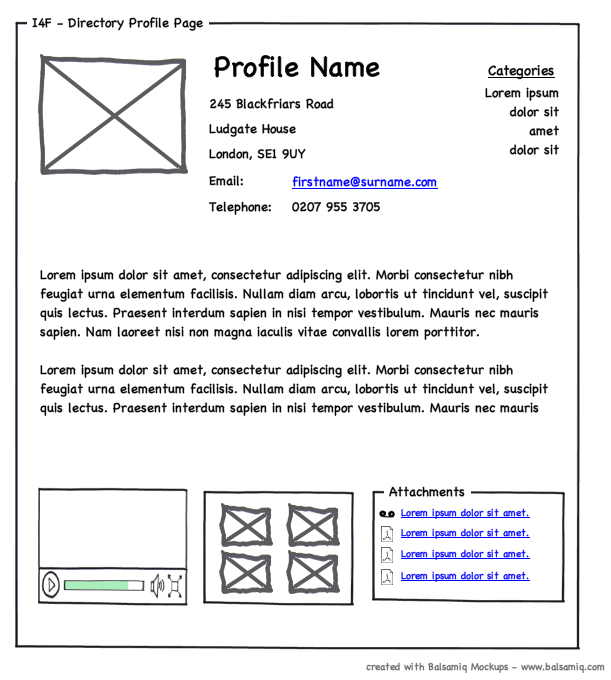

A wireframe is a different type of diagram for analyzing and planning websites and something we have not talked about yet. A wireframe is typically a design tool: a way of sketching the layout for one single page. A wireframe is like the skeleton of a webpage that works to help plan where the main components will go without worrying about the details of those components. Images are typically represented as boxes with "X"es in them. Text can be Lorem ipsum, squiggles, or just lines. Here are two examples:

In the homework for this week, I will be asking you to create a few pages, create links between them in both a linear and nonlinear fashion, and then to create a sitemap that diagrams this web of relations. We'll talk about working with wireframes in later weeks.