Code Toolkit: Python, Fall 2025

Week 4 — Wednesday, September 17 — Class notes

Table of contents for today

- Review of last week

- Conditionals and making things move (on their own)

-

mousePressedandkeyPressed - Conditionals

- Keyboard interaction

- Events

- Making things move (on their own)

I. Review of last week

-

Last week we learned about moving from static compositions that create a single fixed frame, to interactive compositions that can respond to mouse input to create kinetic, moving images. In Processing this is often called active mode.

-

To achieve that we learned some new syntax: the

setup()anddraw()blocks:def setup(): # Things here run once, at the start of your program def draw(): # Things here run many times, once per frame -

In static mode, your sketches ran once in a split second, and then stopped frozen forever, but now, in active mode, your sketches unfold in human time. Because of this, you need to ask yourself when commands will be executed: once at the beginning of your sketch, or once per frame?

For example, with raster images, you want to load them once, at the beginning of your sketch, but you will probably want to draw them every frame. You would do that using the code blocks that you just learned about like this:

def setup(): global img img = loadImage("some-image.jpg") def draw(): global img image(img,0,0)NOTE: This is the pattern that you should use for working with raster images from now on. -

We also saw how to use mouse movement with built-in variables that Processing defines for us:

mouseXandmouseY. -

We also talked about

pmouseXandpmouseY, and we saw how these special, built-in variables give you the position of the mouse from the previous frame. So if you are curious or still confused about that, have a look at the class notes and ask me for help. For example, here is how you could use those two variables to calculate the distance the mouse pointer traveled from one frame to another:distance = dist( pmouseX, pmouseY, mouseX, mouseY )

-

And lastly, we saw how we could use these special variables in

ways that are more flexible and powerful by using

the

map()command. This command transltes or "maps" a value or variable proportionally from one range of numbers to another range. For example, the following code usesmouseXto position a rectangle, but limits its movement to a 100 pixel range:rectangleX = map(mouseX, 0,width, 300,400) rect( rectangleX,300, 50,50 )

The lecture notes from last week show several other examples of this command that you can hopefully use as patterns or templates that you can apply to your own work.

Remember to please include a comment at the top of your code with your name, date, and exercise number. For example:

"""

Your name

Course title & semester

Date

Week number

"""

(jump back up to table of contents)

a. Homework review

In class we reviewed Simarna's homework togther.

We practiced reading her code and deduced that it was choosing a random color once at the start of the sketch and drawing three shapes: one moved horizontally, one moved vertically, and one was a triangle with two hard-coded vertices, and a third vertex that moved left and right with the mouse.

Together we worked out how to use sin() to add

some curved motion to this composition.

First, I explained how sine and cosine work in general terms, recalling principles of trigonometry. The sine function returns a range of values from 0 to 1 to -1 and then back to 0, as its variable (usually shown along the x axis) moves from zero to 2 pi.

In Python / Processing, we can work with that like this:

t = map( mouseX, 0,width, 0,2*PI ) s = sin(t) fill(155,155,255) ellipse(t*75,s*200+300, 50,50)

Note that mouseX is being map()ed

from its minimum and maximum values into the minimum and

maximum values of one cycle of sine, which I

call t, and which we calculate with the built-in

function sin(). Processing also offers us a

built-in variable for pi: PI

Then, we take t as the input

(the argument) for the sin()

function. This way, as the mouse moves from the left to the

right of the window, t will span the range of one

cycle of sine, and the variable s will also go

through one cycle of a sine wave, from 0 to -1 to 1 and back

to 0.

Just drawing that would not yield very much movement because

those values (0 to about 6.28, and -1 to 1) are not very large

values within our draw window. So, we

multiplied t by 75 and s by 200. I

also used addition to shift the wave down in the window

by 300.

Next we talked about how we could add in cos() to

create a circle:

line( 300,300, 300+sin(t)*100,300+cos(t)*200 )

This code uses the same t parameter, so that as

the mouse moves from the left to the right of the window, we

will get values within one cycle of sine and cosine.

If you recall from trig, the x and y coordinates of a circle

are determined by sine and cosine. As the y value of the

circle cycles counter-clockwise through sine values (from 0,

to 1, back to 0, then -1, and then back to 0), the x value of

the circle cycles through the cosine values (from 1 to 0, to

-1, to 0, and back to 1). Thus, we use sin(t) for

the x value of ellipse(), and we

use cos(t) for the y value.

As beore, just using these values would make very small movement. So we manipulated them with multiplication to shift and scale them as we wanted.

You can see the full code here:

week04_week03hw_simarna.pyde.txtThanks, Simarna, for sharing!

II. Conditionals and making things move (on their own)

This week we will build on last week in two ways.

First, we will learn how to use conditionals so that instead of the continuous change of mouse movement, you can create movement that is discrete and discontinuous.

Second, we will build on our use of variables and Processing's interactive mode to create things that move on their own, not only as directly controlled by the mouse.

a. Background

Last week we saw how to make interactive compositions, but they were always moving in continuous, connected ways. Colors that changed as smooth gradients, and shapes that moved, resized, or left trails, but only ever directly correlated with mouse movement.

Today we will see how to work with one of the fundamental principles of digital media which is how to work with discontinuity, or on/off relationships — shapes that appear and disappear, or change their size and locations in discontinuous ways. This kind of behavior is often described as discrete. (Not to be confused with "discreet"!)

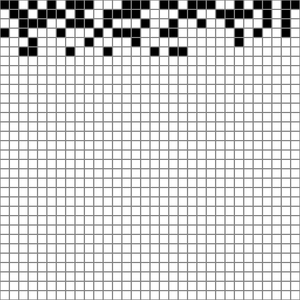

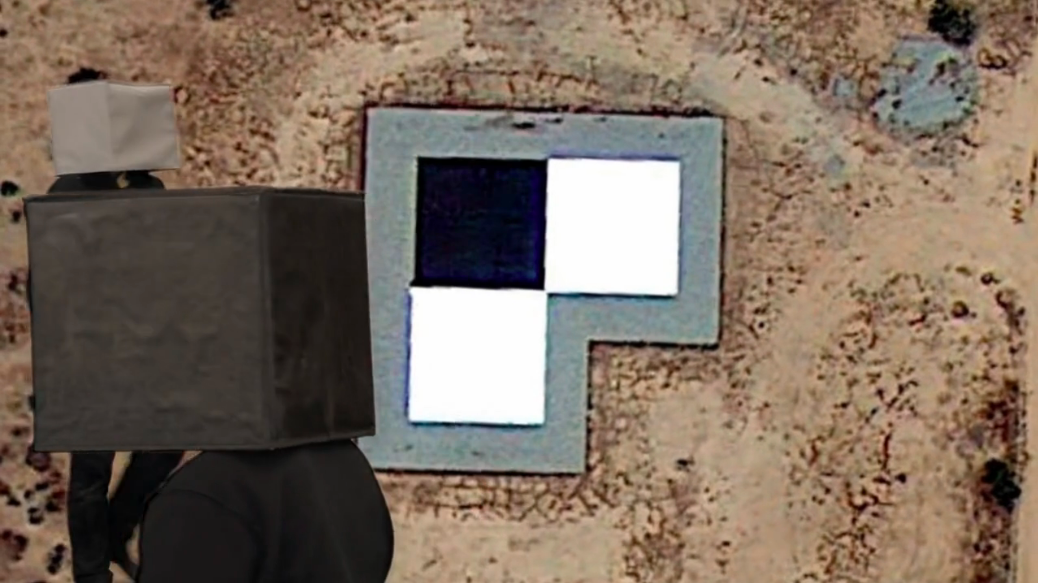

In 1997, the net artist John Simon created a project called Every Icon. This conceptul work enacts a play of combinatorics by starting with the first (top, left) pixel of a 32 by 32 grid, and advances in sequence, creating every possible combination of pixels, or in other works, every possible icon.

To similar ends but in a more poetic and ironic way, the artist Hito Steyerl, in her documentary How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, explores (and blurs) the boundary between the analog and digital, between the physical world and the world of digital representations, or in other words, between the smooth and the discrete.

Let's keep all of this in the back of our minds as we explore the logic of discrete on/off structures today and dive in to binary logic.

(jump back up to table of contents)III. mousePressed and keyPressed

-

In addition to

mouseXandmouseY, Processing gives us some other built-in variables that we can use to create user interaction:mousePressedtells us if the mouse is currently being pressed, andkeyPressedtells us if the any key is currently being pressed

- But what is if? So far, variables have only had numeric values. How can a variable tell us "if" something?

- These variables are of a new kind of value. We say that they are a new type, and it is called Boolean.

-

Just like with the numerical values and variables that we have

been using, Boolean variables can be used

whenever we want to keep track of something. While numerical

variables keep track of quantities, Boolean

variables keep track of things with only two possible

values: yes or no, on or off, visible or hidden. Their value is

always only either

TrueorFalse. So you would use them like this:isDrawing = False

or like this:isDrawing = True

-

Notice that I'm writing

TrueandFalseas valid Python code. That is because they are actual values that you can use in your code just like numbers, which in technical jargon we call literals. So far we have seen numerical literals like 0, 1, 2, 10, 300, etc, and string literals like"hello". Now we have the Boolean literalsTrueandFalse. You can see this if you useprint()to display the value ofmousePressed:def draw(): print(mousePressed) - But how do we actually use these variables?

IV. Conditionals

-

Conditionals are ways of

asking if something is happening or not, and to

allow our code to have different behavior in each

case. Thus, conditionals are often referred to

as

ifstatements. -

Your code can now be more than one simple set of top-down

instructions, and can instead have the possibility of doing

different things depending on various variables, calculations,

and user actions.

A note on pseudocode. (Pronounced, "SOO-doh code".) So far, all the code that I've shown you has been valid Python/Processing syntax. You could copy/paste it into the PDE and it would run. Now we will start talking about a thing called pseudocode. Pseudocode is basically plain English, but with some bits of valid code in it. There are not hard and fast rules about valid pseudocode. Rather, it is a way of writing out an algorithm in English with bits of actual code in it. It is a way to describe an algorithm and work it out, without implementing it yet.

(Pseudocode will always be indicated with a gray background and a thin side border. Remember, this is to help us understand, but you are not able to copy/paste it into the PDE.)If the answer to some question is Yes: then run some commands -

As an example, let's start with this code that draws a circle in the middle of the window:

def setup(): size(600,600) def draw(): background(255) ellipse(300,300, 50,50)Now, let's draw this circle only if the user is pressing the mouse by adding this new syntax for conditionals:def setup(): size(600,600) def draw(): background(255) if mousePressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50)Some new syntax rules:-

You write

iffollowed by a Boolean variable (or an expression that evaluates toTrueorFalse— we'll look at these below). - You do not need to put your Boolean expression in parentheses, but they are optional. Later on when working with more complicated logic, you will see examples in which you will need or want parentheses here.

-

Notice the indentation. The if statement

introduces a new

code block, so after your

Boolean expression, you add a colon, and

the next line must be indented. The block continues until

you stop indenting. The block can contain any arbitrary

Python / Processing statements that you wish, and we say

that all of the statements of this block are

inside this

ifstatement. -

Most importantly: The code inside

the

ifstatement only gets run if the Boolean expression evaluates toTrue.

-

You write

-

Think of this as allowing you to ask questions, like, "Is the mouse being pressed?" I recommend reading the above code in pseudocode in the following way:

If the mouse is being pressed, then draw an ellipse. -

You can combine questions together using boolean operators.

-

and, both parts must beTrue -

or, only one part must beTrue(either or both is fine) -

not, the expression that follows must beFalse

Here are some examples:

if mousePressed and keyPressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50)If the mouse is being pressed and any key is being pressed, then draw an ellipse.if mousePressed or keyPressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50)If either the mouse is being pressed or any key is being pressed, then draw an ellipse.if not mousePressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50)If the mouse is not being pressed then draw an ellipse. -

-

In addition to the special Boolean variables

mousePressedandkeyPressed, you can also ask questions about numbers that you are using in your sketch. Consider the following pseudocode:If the mouse is on the left half of the screen then draw an ellipseLet's get more specific:If the mouse x position is less than 300 then draw an ellipseAnd now let's translate that into real Processing code:def setup(): size(600,600) def draw(): background(255) if mouseX < 300: ellipse(300,300, 50,50) -

The full set of yes/no questions that you can ask about numbers are:

<less than>greater than==equal to<=less than or equal>=greater than or equal!=not equal to (This is equivalent to using==and preceding the entire expression withnot)

-

And just as with

mousePressedandkeyPressed, you can combine these together with boolean operators to ask more complicated questions. Let's start with some basic pseudocode:If the mouse is being pressed in the left half of the window then draw an ellipseGet more specific:If the mouse x position is less than 300 and the mouse is being pressed then draw an ellipse

And finally translate that into valid Processing syntax:def setup(): size(600,600) def draw(): background(255) if ( mouseX < 300 and mousePressed ): ellipse(300,300, 50,50)Try moving the mouse to both sides of the window with and without clicking to see exactly what's happening. -

In the above examples, if the Boolean expression is

False, nothing happens. In other words, if the mouse is not being pressed (to take one example from above) then the code has done nothing. Well let's add another shape:def setup(): size(600,600) # Note that I'm adding the following two lines # so that we can see both shapes together, # and to draw both shapes at the same x,y noFill() rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) if mousePressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50) rect(300,300, 50,50)Note the indendation. Therect()command is not inside theifstatement, so it gets run always. The blank line is not required and I added it only for clarity. As you can see, theifstatement applies only to the cirlce, and the square is being drawn always. What if we only want the square to be drawn instead of the circle, in an "either / or" fashion. Well you could use the logicalnotoperator and write two conditionals like this:def setup(): size(600,600) noFill() rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) if mousePressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50) if not mousePressed: rect(300,300, 50,50) -

But, it turns out that this is such a common thing to do in programming that there is a special syntax for it:

elseYou write this in Python like this:

def setup(): size(600,600) noFill() rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) if mousePressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50) else: rect(300,300, 50,50)I recommend reading that in pseudocode like this:If the mouse is being pressed then draw an ellipse Otherwise, if is not being pressed, then draw a rectangleelseis kind of like saying "otherwise" in English. It is the thing that happens if none of the conditions are met. -

A note on syntax:

-

ifstarts a new conditional block. And any time you seeif, it is not related to past conditionals. So the above example could have looked like this:if mousePressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50) # lots of other commands here ... if not mousePressed: rect(300,300, 50,50)and still been valid. -

However,

elsemust come immediately after anifblock, and it is logically connected to thatifstatement. So this is invalid:if mousePressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50) # lots of other commands here ... else: # INVALID! rect(300,300, 50,50)And instead must be written like this:

if mousePressed: ellipse(300,300, 50,50) else: rect(300,300, 50,50)in which case the logic of theelsemust be understood in terms of the precedingif. In other words, it means "do something if the mouse is not being pressed."

-

-

Sometimes, in your "if not" case (i.e. in an

else:block), you may have other criteria that you'll want to check. Consider this example: starting with the following pseudocode:If the mouse is on the left of the screen then draw a circle If not, If the mouse is in the middle of the screen then draw a square If not, then draw a triangleIn this case, to get more specific, we could say this in two different ways that are both logically equivalent:

Here on the left, we are being explicit about each logical case. While on the right side, we are using the "if not" construction to say: "ifIf mouseX < 200 then draw a circle If mouseX >= 200 and mouseX < 400 then draw a square If mouseX >= 400 then draw a triangle

If mouseX < 200 then draw a circle If not, and if mouseX < 400 then draw a square If not then draw a triangle

mouseXis less than 200, then draw a circle, otherwise (if it is not less than 200) if it is less than 400, then draw a square."This idea of "if not and if something else" has its own syntax, and that is

elif, short for "else if". We would write the above right-side example in the following way:def setup(): size(600,600) noFill() rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) if mouseX < 200: ellipse(300,300, 50,50) elif mouseX < 400: rect(300,300, 50,50) else: triangle( 300,275, 325,325, 275,325)This new syntax (elif) uses the fact that the first part of the conditional (mouseX < 200) isFalse, and then adds another question. So it's like saying "Otherwise, sincemouseXis greater than 200, if it is less than 400, then draw a square." And in this example, the finalelsenow says "Otherwise, sincemouseXis greater than 400, then draw triangle." Note that the order is important here. For example, think about what would happen if we switched the order of the first two conditionals. If you wrote the following:if mouseX < 400: ellipse(300,300, 50,50) elif mouseX < 200: rect(300,300, 50,50) else: triangle( 300,275, 325,325, 275,325)

The square would never get drawn. Why? What would make the firstifstatementFalse? IfmouseXis greater than or equal to 400. But if this is the case, it could never be less than 200. -

If

elifseems confusing to you, that's OK. It is confusing. Even expert programmers get tripped up about these kinds of logical statements all the time, and they are often the source of time-consuming and expensive bugs. Fortunately, you can write this example in a way that is more clear and readable, and that is also logically equivalent — based on the left-side pseudocode above, like this:def setup(): size(600,600) noFill() rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) if mouseX < 200: ellipse(300,300, 50,50) if mouseX >= 200 and mouseX < 400: rect(300,300, 50,50) if mouseX >= 400: triangle( 300,275, 325,325, 275,325)This example is totally clear and explicit about each quesiton that you are asking, and is probably the easiest and most understandable way to implement this. -

As a final example, let's stitch together several Boolean variables to ask a slightly more complicated question.

Let's start again with some pseudocode:

Draw a small square If the mouse is inside this square then draw a circleStart with the basics:

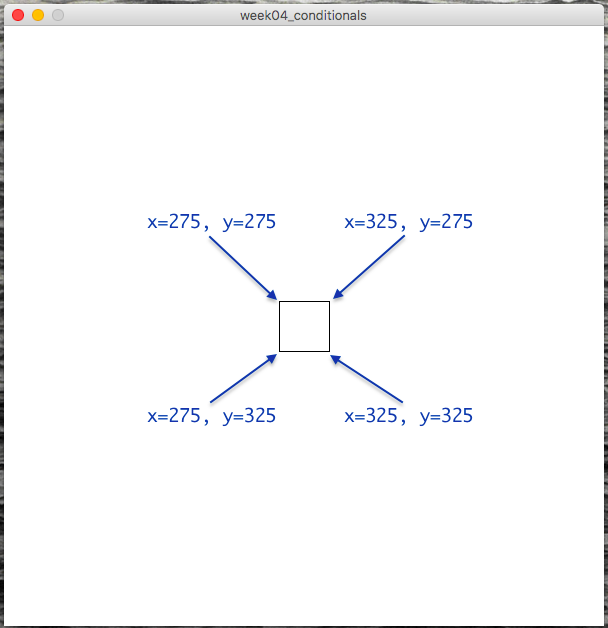

def setup(): size(600,600) noFill() rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) rect(300,300, 50,50)Now before we try to implement the conditional, let's diagram what's going on here:

With these coordinates in mind, let's refine our pseudocode:

Draw a small square If mouseX is greater than 275 and less than 325, and mouseY is greater than 275 and less than 325, then draw a circleIf that's not totally clear, pause for a second and think through the logic of those comparisons to see how that pseudocode describes a check that the mouse is inside the above box.Moving forward from there, we can now implement a conditional for this description:

def setup(): size(600,600) noFill() rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) rect(300,300, 50,50) if mouseX > 275 and mouseX < 325 and mouseY > 275 and mouseY < 325: ellipse(300,300, 50,50)Note that you must write

mouseXtwice. In other words, Python does not allow you to say something like this:275 < mouseX < 325 # INVALID! Sorry :(

You must write it out as:mouseX > 275 and mouseX < 325

In other words, our Boolean comparison operators are binary operators, meaning that they only take two arguments.If you'd like, if it is more clear to you, you could write it like this:

275 < mouseX && mouseX < 325

which is equivalent (note the change from>to<). Personally I find this more confusing, but it may look nicer to your eye.

V. Keyboard interaction

-

So far we've seen how you can use the special Processing variable

keyPressedto let the user press any key to trigger a conditional action. But this only tells us if any key is being pressed or not. What if we want to get more specific and create code that responds to specific keys? -

Fortunately, Processing offers us another special variable just for this purpose:

key. (Processing reference. That says "example is broken", but it actually seems to work OK for me. Maybe there is something I'm missing.)With this variable, we are now working with a variable type that I have mentioned before called a string: a bit of text surrounded in single or double quotes. For example:

'a'or"b". You can read more about strings in the Processing reference, or in the Python reference.Like everything in Python and Processing, strings are case-sensitive, so:

print('a' == 'a') # would print True, but print('A' == 'a') # would print false.Let's add to our example above:

def setup(): size(600,600) def draw(): background(255) if keyPressed: if key == 'e': ellipse(300,300, 50,50)Note that I have added a newifstatement inside the previousifstatement. Programmers call this a nestedifstatement, because one is inside the block of another. It might look complicated, but hopefully if you think carefully about the logic, it is really simple. Let's think about it with pseudocode:If any key is being pressed, if that key is a lowercase 'e' then draw an ellipse. -

Now where this gets tricky is that there are multiple ways to write this same logic. These ways are all valid, and you can use whichever is more clear and readable for you.

In reading that pseudocode, you might have gotten the impression that I could also have written it like this:

If any key is being pressed, and that key is a lowercase 'e' then draw an ellipse.and that would make perfect sense. They are logically equivalent. In fact, I could implement that pseudocode in Processing syntax, and it would also work perfectly well:def setup(): size(600,600) def draw(): background(255) if keyPressed and key == 'e': ellipse(300,300, 50,50)Use whichever form makes more sense to you and is easier for you to translate back-and-forth from your natural langauge to Processing syntax. The important thing to understand is that nestingifstatements is kind of likeandin that both conditional parts must beTrue.Now let's expand on that example and see if you prefer one method or the other. What if we want to add a second key command to draw a square?

def setup(): size(600,600) rectMode(CENTER) # Adding this back for clarity def draw(): background(255) if keyPressed and key == 'e': ellipse(300,300, 50,50) if keyPressed and key == 'r': rect(300,300, 50,50)Adding more key commands would simply repeat that pattern. And maybe now you can see here why writing it this way for many key commands might be a little bit annoying. You have to add thatkeyPressed andcheck every time. Programmers usually hate redundancy like this and prefer to write things only once if possible, as it makes code less prone to errors.Let's change it back to the previous style. Making a change like this is called refactoring. This is a fancy word that programmers like to use that just means re-writing code in a way that is equivalent and usually clearer or more efficient. So let's refactor this example:

def setup(): size(600,600) rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) if keyPressed: if key == 'e': ellipse(300,300, 50,50) if key == 'r': rect(300,300, 50,50)With this style, you are only checking that they key is pressed once, and if that isTrue, you have a series of nestedifstatements that then check which character was pressed.

VI. Events

-

In addition to these conditionals using

keyPressedandkey, there is even an important third way of handling keyboard interaction. Try running the following code and make very quick key presses:def setup(): size(600, 600) frameRate(60) def draw(): if keyPressed: ellipse( random(0,width),random(0,height), 50,50 )My goal was to draw a single circle at a random location each time a key is pressed. But one key press will likely draw many circles. That's because the code is responding to a single key press more than once. Because the frame rate is going fast relative to human reflexes, it appears that the user has pressed the key on multiple frame renderings, or in other words, during multiple executions of thedraw()block.Another problematic example would be if you slow down the

framerate:def setup(): size(600, 600) frameRate(1) def draw(): background(255) if keyPressed: ellipse(300, 300, 50, 50)This is an exagerated example, but it shows that when you are only checking for key presses inside the

draw()block, it is possible that you may not respond to all of them. By pressing keys more quickly than the frame rate refreshes, you are causing Processing to "miss" your action. When the frame is being rendered, you are not pressing the key, you are essentially pressing the key between frames. -

These may be behaviors that you want. But if not, there is another option.

-

A new code block:

def keyPressed(): # commands in hereThis special block is triggered exactly once, every single time a key is pressed. That means that you don't have to worry about it not being called, and you don't have to worry about it being called more than once.Also, inside this new block (which must always be global, outside all other blocks), you do not need to check if

keyPressedisTrue. You know that your code is responding to one single key press.This style of interactive programming is called event handling because your code is handling, or responding to, an event that the user triggers. This is an important part of any game development or user interface coding.

-

Let's look at our previous example implemented in this way:

def setup(): size(600,600) rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) def keyPressed(): if key == 'e': ellipse(300,300, 50,50) if key == 'r': rect(300,300, 50,50)

Sidenote: There is a similar pattern here for the mouse. The(jump back up to table of contents)mousePressed()block is also valid syntax and would be used in a similar way:def setup(): size(600,600) rectMode(CENTER) def draw(): background(255) def mousePressed(): ellipse( 300,300, 50,50 )

VII. Making things move (on their own)

-

Changing topics, let's look at how we can make things move on their own, instead of only moving in response to

mouseXandmouseY, as well as mouse and key presses.This is not a complicated topic and only brings together several things we've already seen, namely: variables, arithmetic, and

frameRate. -

Let's begin with the simple example that we've been starting with:

def setup(): size(600,600) stroke(50,50,150) fill(200,200,255) def draw(): background(255) ellipse( 300,300, 50,50) -

Now if we want that circle to move side to side, what do we need to add? We want it's position to change and to "vary" ... so we'll add a variable:

circleX = 300 def setup(): size(600,600) stroke(50,50,150) fill(200,200,255) def draw(): background(255) ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50 )

Just by itself, this change isn't going to make the circle move. How could we do that? What we've seen so far would be to use something likemouseX. So we could maybe try to modifydraw()like this:def draw(): background(255) global circleX circleX = mouseX ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50 )But what if we want the position of the circle to change "on its own"? -

Using pieces that you've already seen, all we'd need to do is

modify the value of the variable inside

draw()so that it changes a little bit each frame. Like this:circleX = 300 def setup(): size(600,600) stroke(50,50,150) fill(200,200,255) def draw(): background(255) ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50 ) global circleX circleX = circleX + 1

If that new line is confusing for you to understand, try writing it this way, which is equivalent, and maybe a little more clear:

def draw():

background(255)

ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50 )

temp = circleX + 1

circleX = temp

That might clarify what may to you look like circular logic of

assigning that variable to itself.

But! The circle disappears! How can we make it come back? Let's make it so that if the circle moves off to the right, we have it re-appear at the left. To do this, let's think through some pseudocode:

Draw a circle at location circleX

Increment the value of circleX by 1

If the circle goes off the window to the right

then redraw the circle on the left.

Or, getting more specific:

Draw a circle at location circleX

Increment the value of circleX by 1

If the circleX > width

then circleX = 0

Now it should be pretty easy to translate this into valid

Processing syntax:

circleX = 300

def setup():

size(600,600)

stroke(50,50,150)

fill(200,200,255)

def draw():

background(255)

ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50 )

global circleX

circleX = circleX + 1

if circleX > width:

circleX = 0

Nice! I'm sure with a little adjusting, you can modify that so

that we let the circle completely disappear, and then re-appear

smoothly. (Hint: you can set circleX to a

negative value.)

In class, Angel asked how we might have the circle appear on the

left side smoothly as it was disappearing off the right. The

answer of course is to draw two circles for some short amount of

time. Here is the code we worked out to do that:

circleX = 300

def setup():

size(600,600)

stroke(50,50,150)

fill(200,200,255)

def draw():

background(255)

ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50 )

global circleX

circleX = circleX + 1

if circleX > width + 25:

circleX = 0

if circleX > width and circleX < width + 25:

ellipse( circleX-width-25,300, 50,50)

Let's get a little more complicated. What if we don't want the circle to re-appear on the other side, but rather to "bounce" off the wall of the window? Now, instead of only moving to the right, sometimes we'll want the shape to move to the left. In other words, we want the direction of the circle to change. And when we want something to change, what do we need?

A variable.

So let's add a new variable for the direction of the circle:

circleX = 300 circleDirection = 1 def setup(): size(600,600) stroke(50,50,150) fill(200,200,255) def draw(): background(255) ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50) global circleX circleX = circleX + circleDirection if circleX > width: circleX = 0So far nothing has changed. I've merely swapped in a variable for a hard-coded value. But now, instead of changing the position of the circle when it hits the wall, I want to change the direction. Like this:

circleX = 300

circleDirection = 1

def setup():

size(600,600)

stroke(50,50,150)

fill(200,200,255)

def draw():

background(255)

ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50)

global circleX

global circleDirection

circleX = circleX + circleDirection

if circleX > width:

circleDirection = -1

Great. But now it disappears off the left side. How do we fix this? Do we need a new variable? To answer that, ask yourself: is anything new is changing? No, nothing new is changing, so we don't need a new variable. But we want to change when and how that variable changes. In order to do that, there is another question that we want to ask and respond to. Let's work through the pseudocode:

Draw a circle at location circleX

Increment the value of circleX by 1

If the circleX > width

then change the increment to -1

And how do we want to modify this?

Draw a circle at location circleX

Increment the value of circleX by 1

If the circleX > width

then change the increment to -1

If the circleX < 0

then change the increment to 1

Looks like we need another conditional. Let's add that:

circleX = 300

circleDirection = 1

def setup():

size(600,600)

stroke(50,50,150)

fill(200,200,255)

def draw():

background(255)

ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50)

global circleX

global circleDirection

circleX = circleX + circleDirection

if circleX > width:

circleDirection = -1

if circleX < 0:

circleDirection = 1

Great!

Let's add one more thing. Let's allow the user to

also change the circle direction by pressing some

keys. Let's use 'j' for left and 'l' for right. All we

need to add is the keyPressed() block and two

conditionals:

circleX = 300

circleDirection = 1

def setup():

size(600,600)

stroke(50,50,150)

fill(200,200,255)

def draw():

background(255)

ellipse( circleX,300, 50,50)

global circleX

global circleDirection

circleX = circleX + circleDirection

if circleX > width:

circleDirection = -1

if circleX < 0:

circleDirection = 1

def keyPressed():

if key == 'j':

circleDirection = -1

if key == 'l':

circleDirection = 1

And now, believe it or not, you have all the basic pieces to implement a game like Pong. To be clear, Pong combines many of these elements in a way that may still appear complex, but you should be able to look at this code and have some understanding of what is going on. Take a look:

Maybe try messing around with that a little bit this week as you work on the homework.