Code as a Liberal Art, Spring 2024

Unit 3, Lesson 3 — Tuesday, May 7

Adding interactivity with JavaScript

So far this unit we've talked about HTML and

the .html file as

a page or document, serving as

the atomic unit of the web, and the link as the

object that acts as its connective tissue, creating

relationships and associations between these pages, manifested

as clickable text and images.

We've talked about the way that HTML is oriented toward defining the organizational or semantic structure of a page, while CSS is used to specify aspects of the visual presentation of those pages.

Today we'll talk about a third component: JavaScript, a programming language created for the web, used to add forms of interactivity to web pages that goes beyond merely clicking on links.

Review

Last week we talked about how to add CSS to your pages through three methods:

-

Inline, like this:

<h1 style="color: red;">Header</h1>

-

Internal, like this:

<head> <title></title> <style> h1 { color: red; border: solid 1px; } </style> </head>

-

and External. The preferred method. Like this:

<head> <title></title> <link rel="stylesheet" href="css/style.css"> </head>

CSS itself, whether inline, inside a <style>

tag, or in its own .css file, is made up

of rules, which are structured like this:

h1 { color: red; }and are comprised of a selector, a property, and a value. Selectors can be: HTML tag names, classes, or IDs.

A class is like a group, it defines a collection of HTML elements, while an ID uniquely defines one HTML element on the page.

A given HTML element can have multiple CSS classes, in which case they would be separated by spaces. For example:

<h1 id="title1">Header</h1> <div class="column"> <p class="body-paragraph first-paragraph">A paragraph of text</p> </div>Here you can see an HTML element (

h1) with

an ID, an element (div) with

one CSS class, and a third element

(p) with more than one class.

You target or select various HTML elements in CSS using the selector. Here is some CSS, corresponding to the above snippet, that targets HTML elements in different ways:

h1 {

font-size: 18px;

font-weight: bold;

}

div.column {

width: 50px;

}

.body-paragraph {

font-size: 12px;

line-height: 15px;

}

.first-paragraph {

margin-top: 10px;

}

#title1 {

margin: 5px 0 15px 0; /* specified in order clockwise: top, right, bottom, left */

}

Notice here that I have four different types of selector:

specifying just h1 will

select all h1 elements on the

page, div.column will select

only div elements with

class column, the next two rules will

select any HTML elements with those classes,

and #title1 will select any element

with this ID (in valid HTML this should only match one element).

Remember that comments are added with this

notation: /* */, which must also always

come in pairs, can span multiple lines, and can be placed

anywhere within your CSS code.

- JavaScript: history & context

- Getting started with JavaScript

-

jQuery's

toggleClass()function -

this(teaser)

I. JavaScript: history & context

JavaScript is a programming language that runs inside web browsers. It was invented in the mid-1990s by a programmer named Brandon Eich at the company Netscape, the first company to market a commercial web browser. JavaScript was created as a way to add interactivity to the World Wide Web, which, as I've mentioned, originally emerged primarily with a document-based paradigm.

(a) JavaScript is not Java!

The name JavaScript is somewhat unfortunate because it has

little to nothing to do with the Java programming language,

other than the historical coincidence that they both emerged

around the same time. Originally, the Java programming language

supported things called Applets, the name signifying small

applications, another word for a self-contained computer program

installed on a computer. Applets were (past tense because they

are not really used any more) small, self-contained programs

that could run inside browsers. Presumably, Netscape named its

new programming language JavaScript to signal that it also

offered customized programming capacities in the browser, but as

a scripted language that was more flexible and better integrated

with the browser than self-contained applets. Java Applets had

to be compiled on a desktop computer to generate binary files,

which were then embedded into a webpage, much like how you have

embedded images, video, or audio. JavaScript on the other hand

is an interpretted language, like Python it is

not compiled in advance but interpretted real time, when it

issues run. But where Python is

commonly interpretted by running a command

like python on the command line,

JavaScript is interpretted by the browser itself.

(b) JavaScript's rise to prominence

JavaScript got off to a rocky start. It was unevenly supported across different browsers, and trying to write JavaScript in the early days often entailed debugging different issues that different browsers would introduce. Eventually more widely-accepted standards emerged that more browsers came to implement, and various libraries were introduced that abstracted away these browser inconsistencies in a modular way (remember discussions about abstraction & modularity in the Jean-François Blanchette reading, week 13) allowing programmers to write code that would automatically detect and handle browser differences. One of these libraries is jQuery, which we will be working with today.

In the ensuing decades, the Applets that Java supported started to feel bulky, awkward, and disconnected from the browser and the web pages in which they were embedded, while JavaScript only became more seamlessly integrated with HTML and CSS code. Most browsers no longer support Java Applets, although Java remains a widely popular language for writing standalone desktop applications, mobile apps, and most popularly, so-called "enterprise software" implementing business management systems on servers. JavaScript meanwhile has become so popular that now it runs in many contexts beyond just the web browser, including also server contexts and even on the command line.

(c) Blurring the line between front-end and back-end

If you recall Miriam Posner's article ("JavaScript is for Girls") she described a dichotomy between "back-end" and "front-end" coding, with the former being things like Python and data processing, and the latter being things like JavaScript and CSS. Nowadays, this distinction is becoming blurred by new JavaScript libraries (like Node.js®) that allow JavaScript code to be run in both contexts.

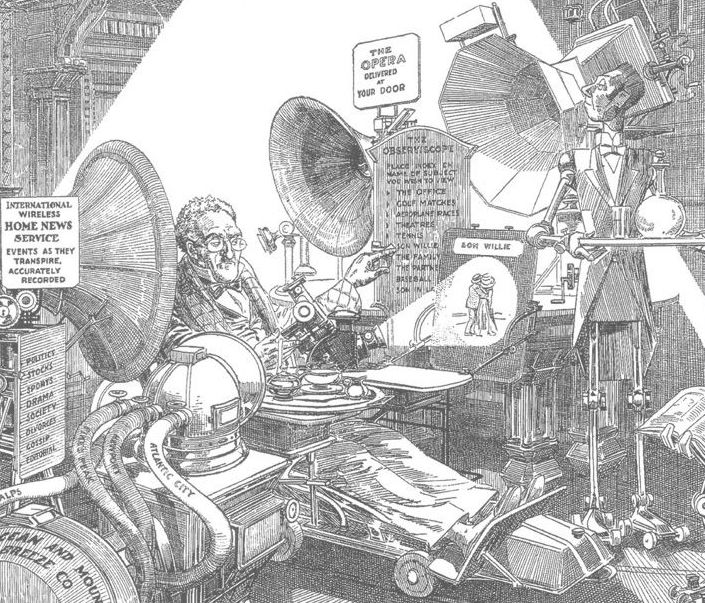

A Rube Goldberg machine is an unnecessarily complicated

mechanical device to accomplish a simple task, often

represented with this aesthetic. I thought it an apt visual to

conjure while working with JavaScript and jQuery. I'm not sure

this sketch is precisely a Rube Golderg machine, but I always

think of it that way. It depicts an imaginary machine for

displaying many types multimedia content so I thought it

particularly fitting for this week. It seems somewhat like

Vannevar Bush's Memex, but updated for a multimedia

environment. The image is from the cover of a book

titled Media

Archaeology Approaches, Applications, and Implications

(Huhtamo & Parikka, 2011) which I can highly recommend if

you're interested in the history of media technology.

A Rube Goldberg machine is an unnecessarily complicated

mechanical device to accomplish a simple task, often

represented with this aesthetic. I thought it an apt visual to

conjure while working with JavaScript and jQuery. I'm not sure

this sketch is precisely a Rube Golderg machine, but I always

think of it that way. It depicts an imaginary machine for

displaying many types multimedia content so I thought it

particularly fitting for this week. It seems somewhat like

Vannevar Bush's Memex, but updated for a multimedia

environment. The image is from the cover of a book

titled Media

Archaeology Approaches, Applications, and Implications

(Huhtamo & Parikka, 2011) which I can highly recommend if

you're interested in the history of media technology.

II. Getting started with JavaScript

I've created some files for us to work with to get

started. Download this .zip file

and uncompress it. That should create a folder

called interaction. Now open up VS Code, close any

other tabs or panes you have open, and drag

the interaction folder into VS Code to open these

files.

Let's get started by looking at the HTML file

called boxes.html and the corresponding CSS

file, boxes-style.css. This creates a layout of

nine boxes that float left. I've filled this with lorem ipsum

but you hopefully imagine how these could have images or other

multimedia, and could perhaps be sized differently to

accommodate more interesting content. Double-click on this to

open it in your browser. You can uncomment

the div rule in the CSS file to see the

borders of the boxes here.

Let's add some interaction here.

To get started with any JavaScript, you have to include the

JavaScript code somehow in your web page. Like CSS, JavaScript

can be included in a web page in more than one way: internal

directly in a <script> tag, or external with

a <script> tag that references a

separate .js file. We'll focus on the second method

today.

Edit boxes.html and inside

the <head> section, add the following code to

include the JavaScript file that I've created for this:

<script src="js/boxes-interaction.js"></script>

We're going to be working mainly with jQuery today. As I mentioned, jQuery is a library that uses abstraction to hide many differences across browsers to make it easier for you write one set of JavaScript code that will work well across browsers, and it also provides a lot of really useful shortcuts for handling user interaction and creating various dynamic effects.

To be able to access all the jQuery functionality, you have to also include the jQuery JavaScript library in your code somehow. There are two main ways you can do this: either download the entire jQuery library and include it in your page just like we have done with this one JavaScript file, or, you can include a reference to this jQuery library that is already hosted somewhere else on the web, on a server called a CDN (content delivery network). We'll do the second method. You can read more about downloading versus using a hosted CDN on the jQuery website, including various URLs to use for CDN-hosted files and different versions of the jQuery library.

The URL we'll use today is for the "slim minified" version of jQuery 3.x. The code to include this is here:

<script src="https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/3.7.1/jquery.min.js" crossorigin="anonymous"></script>Include this in the

.html file above the

previous <script> line, and modify that so it

is all on one line.

Now, from in your JavaScript code you have access to the complete jQuery API, documentation of which is available at api.jquery.com.

Now let's look inside js/boxes-interaction.js. Right now this

only contains one block:

$(document).ready(function(){

});

I'm going to be honest: I find JavaScript to be very difficult to explain to students terms of its general syntax and paradigm - i.e., the general accepted patterns and conventions of how people work in that language. JavaScript is what we would call a functional programming language. It is more oriented around functions (also referred to as subroutines, methods, or procedures) as the primary organizing element. This technique tends to be more modular (again, recall the Blanchette reading) in the sense that it is centered around self-contained, isolated bits of code that are reuable in order to prevent the redundancy of having to write very similar code over and over again.

But this typically creates a type of syntax that I find to be very awkward — for example, in comparison to Python. The main thing to think about is that you can define a function (subroutine) just like you can in Python, but that you can also pass functions as argument in to other functions. (Sometimes people describe this ability to pass functions as arguments by saying that "functions are first class".) You can do this in Python as well, but it is not as common and not as important in Python as it is in the JavaScript paradigm.

Just like in Python, you define a function by writing a bunch of statements, each on their own line, and giving them a name that groups them together. You can then use that name later on to invoke that entire group of commands.

In JavaScript however, you often need to

define anonymous functions: functions that you

never give a name to, instead, defining them simply

as function. These anonymous functions can then be

passed in to other functions. Let's look at an example.

The first line that you see

in js/boxes-interaction.js right now is doing two

important things:

-

The jQuery function

$() -

the

.ready()function, which takes an anonymous function that runs when the HTML page (the "document") has been loaded, and is ready - i.e., the code has been parsed, the DOM has been constructed, etc.

Add this inside the $(document).ready(function(){ });:

$(".select-theme1").click(function(){

$(".theme1").toggle();

});

This is specifying up an event. User interface programming, like the interactive coding that we are now doing with JavaScript, is often cetnered around event-handling. An event is some kind of interactive action that we say is triggered by a user. When an event is triggered, it is then responded to by an event handler. Interactive coding with JavaScript is all about defining these event handlers for specific events.

In the above example, I've defined an event

handler for a click event (a mouse click) on all HTML

elements with the class select-theme1. When this

event is triggered, this code will be called,

and it will toggle all HTML elements with

the theme1 class — by toggle I mean show if

it's hidden, or hide it if it's being shown.

How would you replicate this for the other bits of text in our example that I want to be clickable?

$(".select-theme1").click(function(){

$(".theme1").toggle();

});

$(".select-theme2").click(function(){

$(".theme2").toggle();

});

$(".select-theme3").click(function(){

$(".theme3").toggle();

});

III. jQuery's toggleClass() function

What I consider to be one of the most powerful jQuery functions

is toggleClass(). You can read more about it in the

jQuery documentation here: toggleClass().

This function allows you to toggle whether the specified class is applied to a given element or not. In other words, when you call this function, it will apply the class if it is not currently applied, or remove the class if it currently is applied.

This is hugely powerful because now any visual elements that you can define with CSS can by dynamically added or removed. This allows you to enable the user to dynamically change the appearance of anything on the page. Remember that CSS is really powerful and can affect visuals like color, but also layout things like size and spacing.

Here's an example we could add to this above code:

$("div").click(function(){

$(this).toggleClass("bananas");

});

This would also require us to add some additional CSS code to

our css/boxes-style.css file:

.bananas {

background-color: yellow;

}

This applies an event handler to

the click event

for all <div>s on the page. And what

does this event handler do when the

user triggers this event?

It toggles the class that I've

called bananas. This means it would apply or remove

the bananas class, which would apply or remove the

style properties that that class defines.

IV. this (teaser)

But what is this? Notice the

keyword this in the above code snippet. What is

that? We'll talk about it next class ...